This article was commissioned by the ISBA for the July 2019 edition of The Bursars Review.

July 2020. Fandangle Hall School. Somewhere in the UK.

Ali Frankley, new-ish Bursar of Fandangle Hall School on her first assignment after the ISBA[1], had developed a worrying recurring dream. In it, she is running alongside a herd of migrating Wildebeest as they make for the Mara River in the Serengeti. The noise and dust are incredible as they head down the bank, towards the murky brown water, where the crocs are lurking – waiting to pick them off. Then she is suddenly standing on the far bank, screaming at the Wildebeest with all her might not to try to swim across. But she watches in despair as the herd presses on and the unlucky ones are picked off by the crocs, which thrash their tails and roll and roll, dragging the doomed creatures down. As thousands make it across and come past her, in what seems like a miracle of survival, one of the Wildebeest turns to her and says ‘I know it’s crazy, but we can’t help it. It’s the system. We have no choice.’

————————————

‘Ali. Ali, are you alright?’ It was John Reese-Noble on the phone, the Chair of Governors, who, despite a fearsome reputation, was in practice a thoroughly reasonable and pragmatic person.

‘Sorry John. My mind was wandering for a moment there,’ said Ali.

‘Hmm. So – as you very succinctly put it at the last meeting, Ali, we do need to be sorting out what we are going to do about the Climate Change issue. We need a plan. Even if we cannot in practice do very much – which I personally do not believe – we need to plan it; and resource it.’

Ali knew where this was going. The tasker was always preceded by the flattery.

‘I know you did a module on it at the ISBA. Could you produce a short paper for us to consider at the next meeting of the F&GP. I’ll give this my full backing and there’s obviously a core of like-minded souls on the Main Board, which will help a lot. As you have said, like it or not, we’re at something of a crossroads now.’

That evening, Ali set to. She chose as her title: ‘Net-zero carbon by 2025. A plan for the future financial wellbeing of Fandangle Hall School’…

Now, Dear Reader, please fast forward to Scenario One or Scenario Two below. But you can’t choose both: you are at a crossroads.

Scenario One – July 2025 – Fandangle Hall School

Ali beamed with unconcealed happiness as the local MP cut the ribbon on the new minibus and the assembled audience of governors, parents and staff applauded. But the applause was not really about a minibus, which – let’s face it – is only just slightly more interesting than a plantroom in the school cellars. It was the significance of this particular minibus: it was the last to arrive of the new fleet of electric minibuses. The old diesel fleet had all gone. And it meant that the school estate was now officially net-zero carbon for heat, power and transport.

This was thanks in large part to Ali’s efforts, backed up by an inner circle of supportive governors and an enlightened HM. There was no doubting it had been a hard slog, but by a combination of forethought, planning, tenacity, resilience, charm, tact, diplomacy, effort, and maybe just a touch of cunning and gamesmanship – in short, all the traits of every good bursar – she had done it. Fandangle Hall School was the first net-zero carbon school in the country. Go back 10 years and nobody would have known what the term meant, let alone care about it. But now it was 2025 and everybody cared: students cared, parents cared, staff cared, the media cared – even Dear Reader, that former bastion of Climate Change denial, the Daily Mauling.

Ali reflected on the milestones (you might find them a useful aide memoire too):

School Year 2020/21.

She and John Reese-Noble had hatched the plan. She had secured some useful impartial expert support and a school Climate Change Task-Force had been established, with membership from across the community, including parents.

They had established 3 principles of operation:

- Carbon reduction was to be considered in every school plan or procurement programme, no matter how trivial.

- The entire school community was to be involved in the net zero-carbon campaign, and everybody was to be encouraged to come up with ideas and input.

- Carbon reduction progress was to be reported monthly at the SLT and at each termly Governing Body meeting; plus it was to be displayed widely around the campus so that students and staff could see on a daily basis how progress matched the various targets.

In Ali’s plan she had noted how although energy seems like a minefield, in fact – for strategic purposes – the management of it falls into three broad categories: buy well, use well, generate well. Suddenly it did not seem quite so daunting.

She had realised that in order to sort out the power side of things all she had to do was procure 100% renewably sourced grid power. At a stroke this would make all the power usage on the estate zero-carbon. In the end she had sacked her old broker and found a new one, who secured her zero-carbon grid power at no extra cost compared to so-called ‘brown’ power. (He also showed her all his accounts and profit margins, which seemed a good idea).

She had realised that in the ‘Use Well’ category there was no end of things that could be done, but here again, it could be broken down conceptually into bite-sized chunks:

- Chunk One. Sorting out the infrastructure. She got an energy assessor in to do a site-wide energy efficiency survey. This resulted in her having a list of practical technical and energy management interventions the school could make, in order to use a lot less energy.

- Chunk Two. Sorting out behaviour. If staff and students could be persuaded to change how they acted, a lot less energy could be consumed. Fortunately the school was supported by a very dynamic Deputy Head, who took charge of Chunk Two, with resounding success over the next few years.

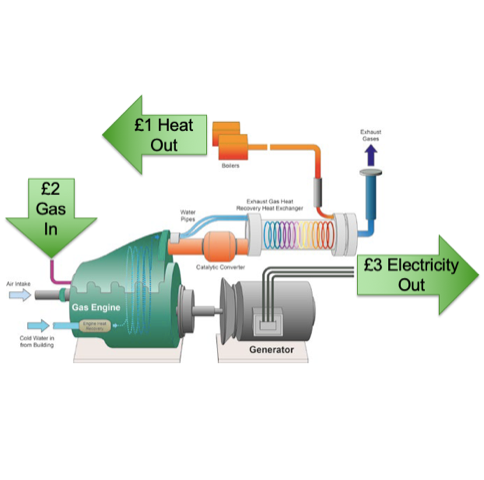

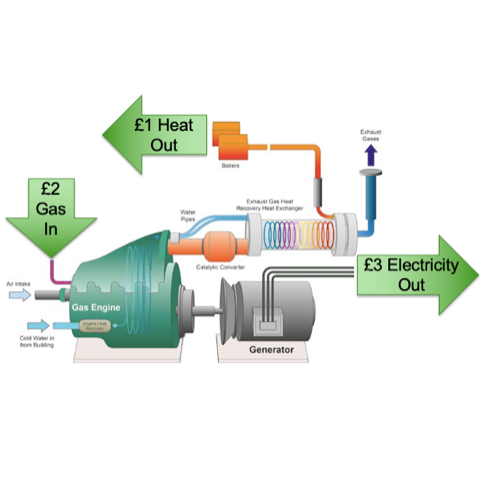

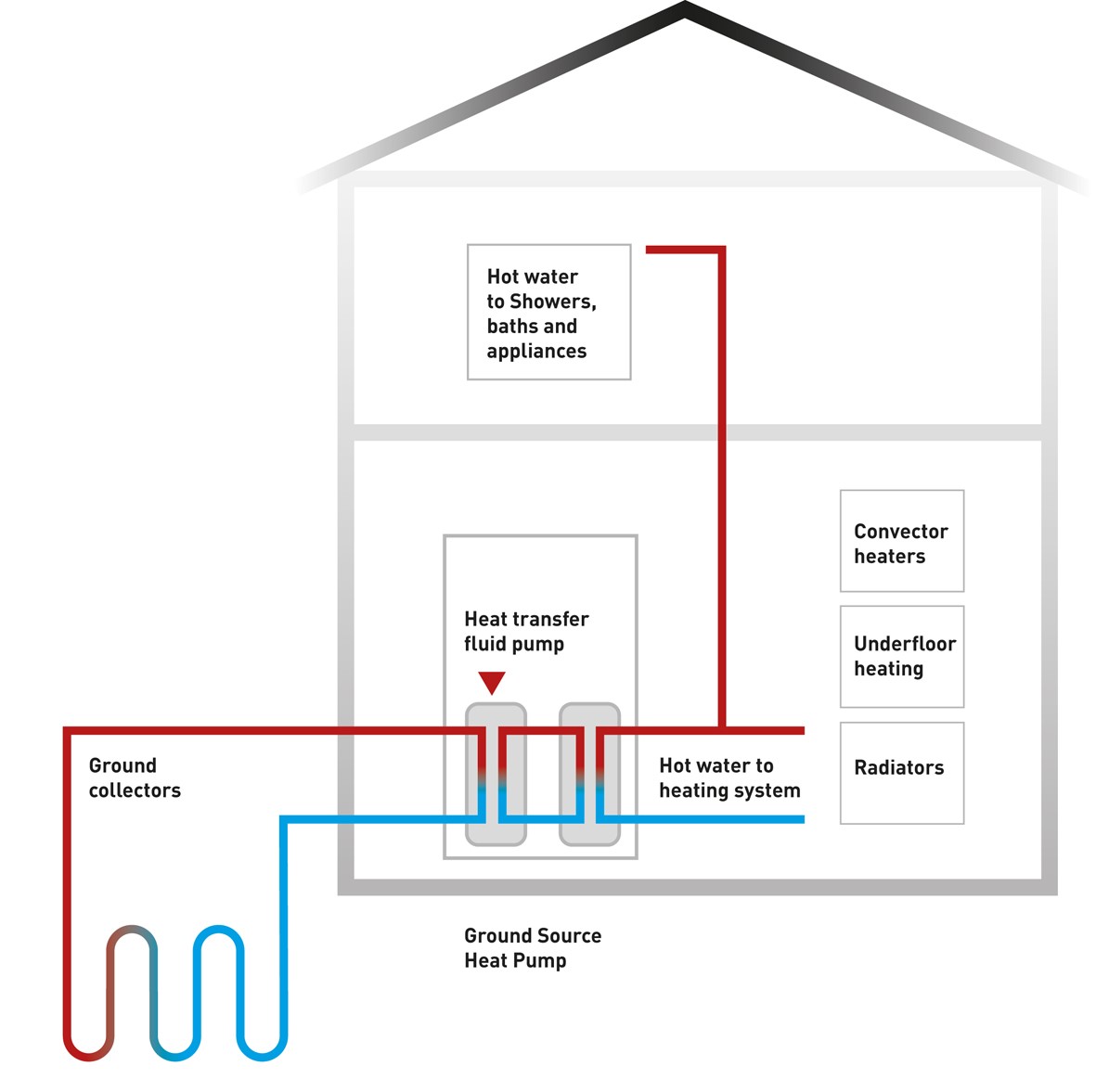

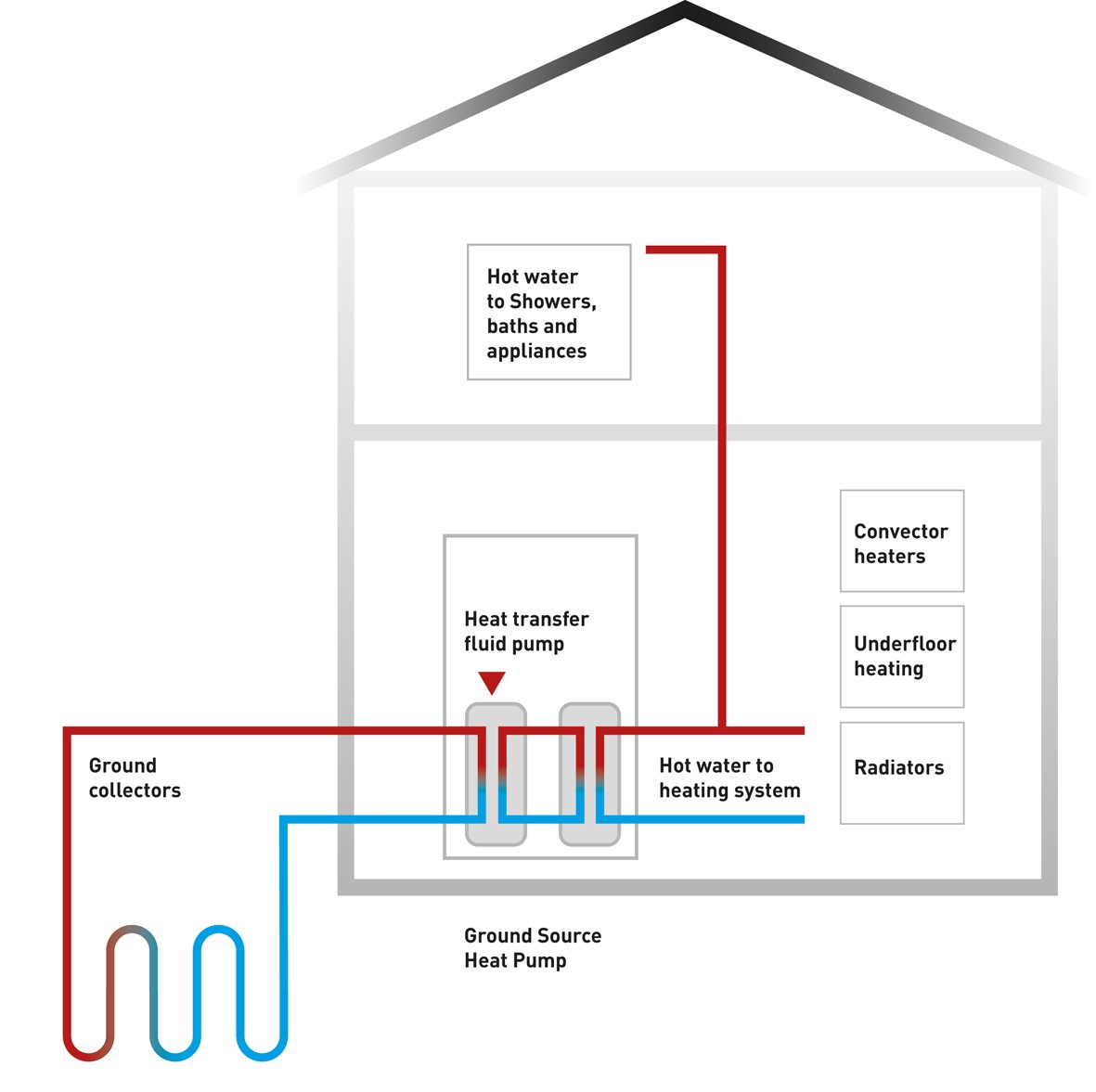

Under the heading of ‘Generate Well’, they had postponed a new build by one year and switched the funds into a zero-carbon heat programme. They had converted all the plantrooms to Ground Source Heat Pumps (GSHP) in time to have them working by the 31st March 2021 subsidy entry deadline (netting the school a cool £5M over 20 years from the UK Government and making the transition affordable). Just to be on the safe side they’d retained some of the old plant (but 5 years later it had all gone – no longer required). It had been a close-run thing, because these low-carbon heat projects cannot be done in a hurry, but like the Prussians at Waterloo they had got there in the nick of time. If only they’d started in 2019 it would have been so much easier – but at least they did it.

Ali also noted that the Sun was still free of charge, and that for each kW in capacity of solar PV installed she would be saving herself potentially a kWh of grid power, per hour of daylight[2]. As grid power was now priced at 12p/kWh ex VAT and rising annually, this was a worthwhile piece of additional power generation on site.

The ISBA had started running a Climate Change & Sustainability Advisory Board for bursars, and Ali had found herself on it. This proved to be a most useful forum for helping each other along; it also had some helpful industry types on it, one of whom, she noticed, seemed to have shares in Hotel Chocolat.

School Year 2021/22.

She and her staff had started working their way through the menu of improvements recommended in the previous year’s energy efficiency survey. They had also focused on the challenge of rendering all the school’s transport zero-carbon. It turned out that transport was going to be the hardest part. Power was already sorted. Ditto heat, by means of the combination of GSHPs and green power from the National Grid to run them. But transport was more difficult. They had already started a programme of EV charging points on the estate, linked up to the solar PV arrays and a bank of storage batteries that had at last become commercially viable. Now they started investigating the options for procuring school EVs.

More broadly in the independent sector, the ISC had finally realised that it should include Sustainability as a heading in the school inspection format. This had had an immediate impact on the rate of change in the sector and put a strain on the supply side; but fortunately Ali was ahead of the curve.

School Year 2022/23. The school transport conversion programme started, with some help from a fundraising campaign, which proved surprisingly popular amongst parents and alumni; (or maybe not so surprising, considering that by then everybody was starting to worry a lot about Climate Change).

School Year 2023/24. Nothing much to report here, except that Ali noticed that a lot of her peers in other schools now seemed a lot more stressed about these things than she was. For one thing, prospective parents nearly all wanted to know what schools were doing about Sustainability and Climate Change. But, Dear Reader, smugness is not an official characteristic of the good bursar, and Ali put it from her mind, whilst quietly smiling to herself and having just one more chocolate brownie with her coffee that morning.

School Year 2024/25. With the arrival of the last of the new EV minibuses, the transformation to the Green Side was complete, and the school had become more successful and prosperous than Ali could possibly have imagined back in 2020.

Scenario Two – July 2027 – Fandangle Hall Hotel

Dear Guest,

Welcome to Fandangle Hall Hotel. Here you will find everything you need for an enjoyable stay in this latest acquisition of the de Vour Group…

There were tears in Ali’s eyes as she read the introductory words in the Hotel Information Booklet in Reception. She looked around. It was amazing what they had achieved in just one year, since they’d bought the site.

Ali reflected how it was nobody’s fault really. It was such a competitive market in the independent sector and the school had just not been able to maintain an edge. The final straw had been the change in regulations relating to fossil fuels and the requirement, in late 2023, to start the transition to low-carbon heat without the benefit of the previous subsidy regime. It had proved to be an expensive process and in Fandangle Hall’s case fatal to the cashflow. It was no consolation that hers was not the only school. If only she and John Reese-Noble had been able to persuade the Governors to make the transition earlier, back in 2020… but that’s a pointless exercise thought Ali, no point in crying over spilt milk.

Above the fireplace in what was now the hotel reception they’d hung a huge oil by Jason Morgan of migrating Wildebeeste crossing the River Mara. Ali was staring at it, when she heard a voice behind her.

‘Can I help you ma’am?’ It was the receptionist.

‘I’m fine thanks. I just came to have a look around. I used to work here, when it was a school,’ said Ali.

‘Well, have a nice day ma’am. Fine painting, isn’t it.’

[1] The Independent Schools Bursar Academy: offering a 3-month preparatory course for new recruits, covering subjects like double-entry book-keeping, patience, plate-spinning, endurance, legislation, compliance, patience, resilience, tact, and a host of other essential bursarly skills.

[2] Contrary to popular belief, the Sun does not have to be shining for solar PV to work, but the rate of energy generation is at its best in full sunlight.